Sawai Tadao

沢井 忠夫

1937 - 4/1/1997

作曲 & 箏

|

Tadao Sawai was born in Aichi Prefecture in 1937. His father was a shakuhachi performer and at around the age of 10 Sawai began to study the koto. In 1959 he was chosen by the Japanese national broadcasting company NHK as the best new performer, and from that time forward he began to be active as a performer and composer of contemporary music. In 1960 he graduated from the traditional music department of Tokyo National university of Fine Arts and Music. He has performed widely throughout Japan and the world and his compositions are among the most widely performed in the koto world. Sawai's Genius Revitalized Modern Koto (From the April 11, 1997 edition of The Japan Times, By Elizabeth Falconer) Some people think of the Japanese koto as a relic of the past; koto music conjures up in their minds a bright, seemingly aimless plucking sound, where the pieces are indistinguishable from each other and seem to go on forever.These people have never heard the music of Sawai Tadao. I first met Sawai in 1986 after a performance in Niigata, when I went to interview him for the Japan Times Weekly. His gentle, unassuming demeanor made it very easy for me to talk to him, and I soon after found myself, through fate of circumstance, continuing my koto studies as a member of the Sawai Koto School. I wrote then that Sawai's music "is dramatic and intense, yet with an element of lightness intertwined, leaving the listener spiritually refreshed." His works have as themes not only the traditional water and seasons often found in koto repertoire but reflect his own perspective of nature that include movement and flight, a feeling of weightlessness; "Tori no yo Ni" (Like a Bird) and "Habataki" (Take Flight) are examples of this. He was also quite moved by the quiet and sometimes brilliant beauty of flowers, and wrote pieces with names such as "Hana Ikada" (Flower Raft), "Manjushaka" (Amaryllis) and "Hyakkafu" (Multitude of Flowers) Pieces such as these have the left and rights hands working constantly, building shifting patterns and utilizing dual rhythms, intertwining textures by using a number of different plucking techniques, some of which he invented and developed. He was a genius when it came to combining soft harmonics and pizzicato with percussive hitting of the strings and tremolos that move across the strings. There is a strength around which the grace of his music is built, and it pulls the listener in. Watching Sawai himself perform the koto was an unforgettable experience; here was all the beauty and control of an instrument brought alive by hands which seemed to pull the music out of the air. Sawai makes playing koto seem effortless. I remember once, when I was lucky enough to be a member of his koto ensemble for his solo concerto in Osaka, some Americans came up afterwards and asked me about the instrument. "How many strings does it have?" they asked. "Thirteen," I replied. "But..." they pointed to Sawai, "That man there, his koto has more strings, doesn't it?" they said. If you have heard Sawai play, you can easily understand their confusion. "No, it's the same instrument. It just sounds like it has more!" Sawai has received numerous awards for his performances, recordings, and compositions, and has performed extensively in Japan and abroad, including North America, Germany, France, Yugoslavia, and the Netherlands. He has composed over 70 pieces for the koto, and while some combine koto with various instruments, from shakuhachi and shamisen to violin and soprano, for the most part he has focused on the koto and bass koto, looking at the instruments from many different angles, working with them as solo and small ensemble instruments of their own merit. For the koto world, struggling to find a meaningful niche in postwar Japan, this has been more than a blessing. It has helped to keep koto alive. Sawai writes for beginners as well as advanced performers: I remember learning Sawai pieces when I was a beginner studying in another koto school back in 1979, and how taken I was with the lively rhythmical elements of his music. It was one of the things that "hooked" me - and I am sure many other struggling beginners - on koto. All of his music is written with a simple goal in mind, which he expressed to me at our first interview, "I want to write music that will make people understand how wonderful koto is." Perhaps his most dramatic work is "Homura" (Bursting into Flames), a bass koto concerto with five-part koto ensemble composed in 1979. The 16-minute work was written for a bass koto recital performed by wife, koto master Sawai Kazue. During the fast-moving piece, the koto ensemble variously bounces drumsticks off the top of the strings, inserts the sticks in between strings and hits them, letting them merrily reverberate, and rubs the top of the strings with drumsticks. The bass koto part finds Sawai Kazue pulling with all her might on the thick bass strings, hitting the strings with the palm of her hand, and rhythmically slapping the sides of the koto as she plays. The piece demonstrates not only Sawai's creative genius and compositional skills, it demonstrates his appreciation for writing music which fits the performer. When Sawai wrote for others, he wrote with their distinct personalities in mind: her performance of the piece brought her the 1979 Geijutsu-sai award. While his performance presence on stage strikes the listener as smooth as glass, his wife Kazue sweats over her instrument, approaching it more like a jazz musician than anything else. Their two approaches can be seen, perhaps, as fine porcelain compared to a piece of raku pottery; both equally artful but different, making the vivid point that the koto, like clay, is utterly malleable in the hands of the artist. Soft-spoken and serene, Sawai held himself at all times with a quiet elegance, as if he were wearing a kimono. He was firm as a teacher, demanding an objective analysis in playing that sharpened one's ears to hear even the smallest unevenness, the most minute of dynamic differences. He had an easygoing nature and laughed easily and often, enjoying the everyday sort of jokes and comedies that arise, often from nervousness, around the head of a very active koto school. Underneath his smooth surface, he was strong as a rock, and weathered many a crisis with dignity and gentle sensitivity. He had a passion for karaoke, and, after a brilliant koto performance, many of his students shared with him this relaxed side of his personality, clapping and singing till the wee hours of the morning. Sawai's most recent recordings include a CD of his works entitled "Sanka" (Song of Praise) on the Kyoto Records label (KYCH-2010) with English and Japanese liner notes and, just out this spring, "Koto Music: Tadao Sawai Plays Michio Miyagi," a Playasound production that includes liner notes in English, French and Japanese (PS 65180). These are both gems, contemporary classical koto music at its finest, and we are lucky to have them available. Sawai Tadao, master of the Japanese koto, founder of the Sawai Koto School, prolific composer, teacher, and visionary leader in the world of Japanese music, died on April 1st at the age of 59.

|

|

教え子

|

アルバム

|

Best Take 2 - Tadao Sawai |

|

Iris of Time |

|

Koto Music - Tadao Sawai Plays Michio Miyagi Sawai plays Miyagi, the most famous of all composers for the koto. |

|

Masterpieces of the Koto |

|

New Hogaku Koto |

|

Nihon no Shirabe |

|

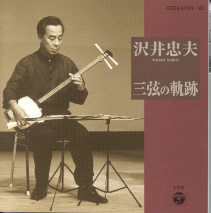

Sangen no Kiseki - 1 |

|

Sangen no Kiseki - 2 |

|

Sanka |

録音した曲

作曲・編曲